Amber downlights cast shadows along the path that leads to the observation deck at Lowell

Observatory.

As we follow the pools of orange light that mark the way up the hill, my brother and sister-in-law and I fold our arms tight over our down coats to ward off the cold of the moonless December night. It doesn’t help.

By the time we reach the deck, the sight of six large telescopes trained on the sky takes our mind off the cold. Below us, the streetlights of Flagstaff, Arizona, have the same feel as the path lights, all part of the town’s designation as a Dark Sky City.

We’ve gathered here for Christmas. When we were planning the trip months before and talking about what we wanted to see, two things were unanimous: the Grand Canyon and Lowell Observatory. Known for its discovery of Pluto by observatory assistant Clyde Tombaugh in 1930, the Lowell Observatory now features one of the finest collections of telescopes available for public observing.

On the circular concrete observation deck, six advanced telescopes are trained on star fields and planets, nebulae and galaxies. At each, a passionate staff member stands ready to share what’s waiting in the viewfinder.

We join a small queue at the biggest telescope first. Hushed voices match the quiet of the night, but visitors can’t help but let out a “Wow!” as they see for themselves another realm brought close enough to see astounding details.

Karl steps up first to view the Owl Cluster, located approximately 7,922 light-years away in the northern constellation Cassiopeia. The two bright stars do indeed resemble the big eyes of an owl.

At the next telescope, Kristin peers into the viewfinder to discover Aldebaran. As the brightest star in the Taurus constellation, it’s one of the eyes of the bull.

The next telescope has three steps up to the viewfinder. The staff member says he’s focused it on the Crab Nebula. I climb the stars and stand on my tip-toes. Closing one eye, I peer through the telescope. The image comes alive. The Crab Nebula. A thrill runs through my body. I’ve heard of this remnant of a supernova for years, seen pictures of it in magazines and on websites. I thought I knew how beautiful it was. But now, seeing it with my own eyes, it is more profound than I’d ever imagined.

It feels so close, yet untouchably ethereal. Timeless.

Wise, even, if a collection of gases and dust swirling around a neutron star can embody knowledge. I gaze into its dazzling color and light, an opal hung in the sky, and I feel a calling. A whisper of connection from 6,500 light-years away. I feel part me is part of the nebula somehow, which sounds crazy, but I can’t shake the feeling that somehow, we’re connected. Family.

I climb down the steps and stand looking up at sparkle of the stars blanketing the sky. There’s Orion. My favorite constellation, the three stars on his belt always reminding me of Christmases past driving across the frozen landscape of Kansas on my way to see my parents. The big “W” of Cassiopeia. The misty edges of the Milky Way.

Seeing the stars gives me both hope and grounding. I’m part of the vastness yet I’m a miniscule speck, and my time here on Earth is but a blink in star time.

But I know each star I see dances a delicate balance between life and death. Just like we do. Each star burns tons of nuclear fuel at their center, creating vast heat. This heat generates pressure, and keeps the star from collapsing under the pressure of its own gravity. In time,

though, the star may run out of fuel and start cooling.

When that happens, the internal pressure starts to decline. When it drops enough, the star can no longer withstand the enormous force of gravity. In seconds, gravity wins and the star collapses. This collapse produces the explosion we call a supernova. What’s left behind is usually a very dense core, along with an expanding cloud of hot gas called a nebula.

The Crab Nebula is the leftover, or remnant, of a massive star in our Milky Way that died. Chinese astronomers and careful observers saw the supernova in the year 1054. I’m seeing it now at the Lowell Observatory on December 26, 2023.

The wind of time sweeps me off the observation deck and drops me softly. It’s 1980. The weekly episode of “Cosmos” on public television has just finished. Karl and I tune in every week, eager to learn more about space, stars, planets from host Carl Sagan, American astronomer, planetary scientist, and science communicator.

I pull on my blue snow boots and orange down coat and step outside. Above our warm stone house, the Colorado winter sky glimmers, silver glitter on an indigo blanket that stretches farther than I can see. Or comprehend. I look up at the stars. I’ve always believed I was made of stardust. Somehow connected through time, through space, through galaxies to all that’s come before, to all that will be.

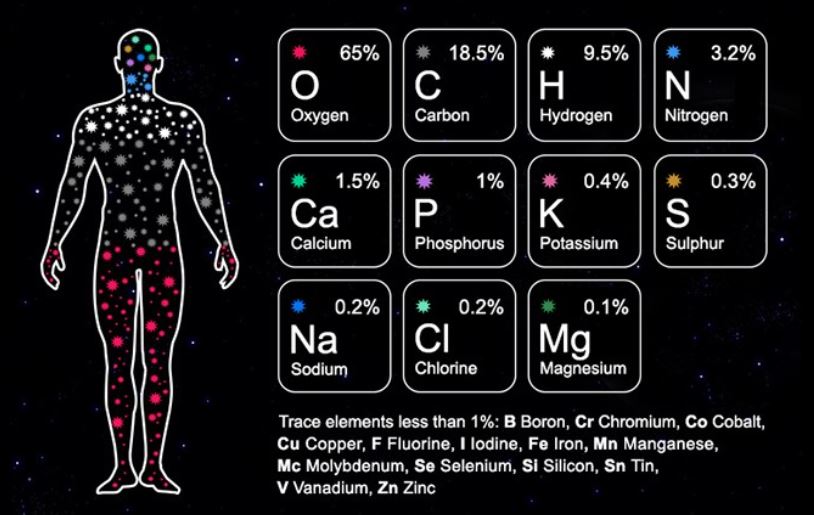

Tonight, Carl Sagan confirmed it. “The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies… were made in the interiors of collapsing stars. The cosmos is within us. We are made of star-stuff. We are a way for the universe to know itself.”

We are made of star-stuff.

The wind picks me up again. I land back at the telescope, the murmur of voices bringing me to the observatory deck. I’m in Flagstaff. It’s 2023.

In the warmth of Karl’s Volvo, we drive back to our AirBnB. The night sky drifts by as I look up from the back seat. Seeing the Crab Nebula tonight has renewed the sense of connection I’ve always felt with the stars. I think about why, and I remember what I learned a long, long time ago on those Sunday nights sitting in front of TV watching “Cosmos.”

When a star dies, the supernova explosion scatters the stardust that is part of every one of us – carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus – into the vastness of space. Stars may cease to be in the form once seen, but their star-stuff remains. Their stardust can even seed a new star.

Maybe our life is like a supernova. Less dramatic, certainly. But perhaps bits of what we were in life, the core of what made us who we are, explode across the vast realm of time and space when we leave this body we’ve called home.

Maybe when we leave this life, pieces of us remain. Our light, like the Crab Nebula, continues to shine.

Maybe the fragment of that moment when we helped the lady navigate her walker across the rough sidewalk raced at the speed of light and transformed into the young boy freeing a hummingbird trapped in the garage.

Or maybe the smile we shared with the harried Mom with the exhausted toddler as we let her go in front of us at the grocery store lit up the sky in another part of the world, a remnant of kindness that lingered on.

Beauty. Light and color. Energy.

Exploding out and out and out and out for infinity. Reaching people we’ll never meet, generations we’ll never know.

Star-stuff. Living on.

=-=-=-=-

Image credit: NASA, ESA, J. Hester and A. Loll (Arizona State University)

=-=-=-=-

More wonder at our shared star-stuff.

“Stars that go supernova are responsible for creating many of the elements of the periodic table, including those that make up the human body. It is totally 100% true: nearly all the elements in the human body were made in a star and many have come through several supernovas.”

Dr. Ashley King, planetary scientist and stardust expert

——-

“Every atom in your body came from a star that exploded. And, the atoms in your left hand probably came from a different star than your right hand. It really is the most poetic thing I know about physics.” Lawrence Krauss, theoretical physicist and cosmologist

——

https://nasa.tumblr.com/post/688583969233682432/you-are-made-of-stardust

https://pweb.cfa.harvard.edu/research/topic/supernovas-remnants